So…well…enjoy!

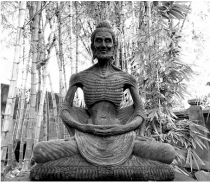

I’ve been sitting on this cushion

Meditating for nine days straight

I’ve been sitting on this cushion

Meditating for nine days straight

Sitting, watching, waiting

To see my Original Face

Everywhere I go

I’m working on that koan Mu

Everywhere I go

I’m working on that koan Mu

I ain’t seen nothing but cows, baby

I got them old Kensho Blues

I’ve been counting my breath

Doing shikantaza too

Walking meditation

Everything else I’m supposed to do

I’m studying sutras

Keeping the precepts day and night

Ain’t nothing happening at all

Am I even doing this right?

Oh No!

That old koan Mu

I ain’t seen nothing but cows, baby

I got them old Kensho Blues

I’ve been to Zhaozhou’s Bridge

Cut Nanquan’s Cat in half

A Dried Shitstick in my left hand

In my right Three Pounds of Flax

I Rolled Up the Blinds

Put Snow in a Silver Bowl

I even took a step off the top of a

One-hundred-foot Pole!

Oh No!

That old koan Mu

I ain’t seen nothing but cows, baby

I got them old Kensho Blues

And I got fed up…

So I got myself a job in a coalmine

Decided kensho just wasn’t worth the fight

I said I’m working in a coalmine

Kensho just wasn’t worth that fight

Check this out:

I don’t need a lantern when I’m down there

Because now everything is shining with light

There’s light in the gutter

There’s light in the sink

It’s flowing like a river

C’mon now – take a drink!

There’s light in everyone’s face

Shooting out of our toes

It’s in the laughing & crying & living & dying

And in the Poconos!

Oh Yes!

That old koan Mu

Now I’m dancing with those cows, baby

So glad I got the Kensho Blues

Everybody!

Now we’re dancing with those cows

So glad we got the Kensho Blues

RSS Feed

RSS Feed